In Search of Gilbert and Idrissa: African Students in the USSR

Sandra Muteteri Heremans

In Search of Gilbert and Idrissa: African Students in the USSR. Artistic Research through the Development of Fictional Characters

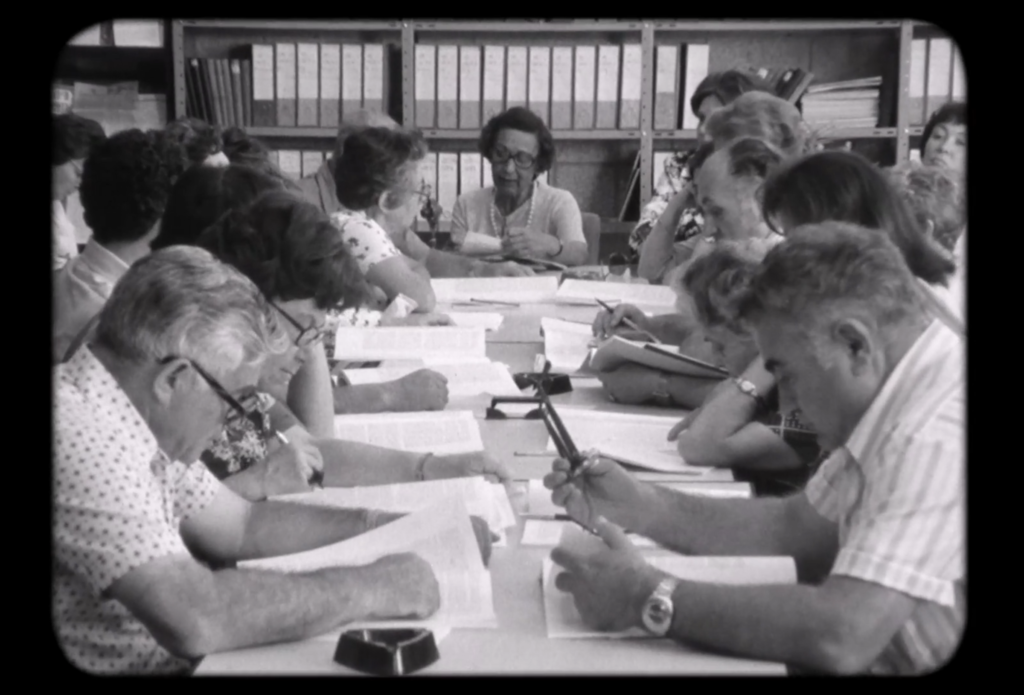

From 1917, during the Russian revolution, all the way through to the late 1980s, the Soviet ideology that advocated Marxist ideals of color-blind internationalism and solidarity among the “oppressed of the world” resonated throughout the globe—including in the colonies, where social and racial inequality were an inseparable part of society. Intellectuals from different parts of the world—on the African continent, the Caribbean, as well as the Americas—saw the Soviet Union as a meeting point and thus a cradle for many communist-inspired revolutionary ideas. For the Soviets the 1950s was characterized by a growing interest in the development of long-term relationships with several countries on the African continent. This happened through Joseph Stalin’s successor Nikita Khrushchev. These stimulating interactions between the Soviet Union and the expanding independence movements on the African continent culminated in the symbolic organization of the 6th World Festival of Youth and Students in 1957, where several delegations of African students were welcomed to Moscow. The festival attracted 34,000 people from 130 countries. Subsequently, on 5 February 1960, the Peoples’ Friendship University of Russia (RUDN University), was established in Moscow. Soon the university was renamed after the murdered Congolese politician Patrice Lumumba and the official name became Patrice Lumumba Peoples’ Friendship University. Students from Asia, Africa, and South America were given the opportunity to become specialists in various fields, in order to contribute to the construction of their newly independent countries.

In 1961, the urgency for education was confirmed during the Conference of African States in Addis Ababa which was dedicated to this issue. Due to a shortage of cadres in the aftermath of the independences, the number of African students in the Soviet Union increased drastically to over 5,000 by the end of the 1960s. Up until the mid-1970s, the Soviets had developed relationships with radical strands of the independence movements in Angola, Benin, Ethiopia, and Mozambique, some of whom fought for their independence with the support of Soviet militias. By 1990, on the eve of Soviet collapse, the number of African students had risen to 30,000, or 24 percent of the total body of foreign students. The reason why students chose to study in the Soviet Union varied from them simply looking for an educational opportunity, to them being attracted by the socialist experiment and looking for an anti-imperialist experience.

My interest in the geopolitical and artistic relations between the Soviet Union and the African continent—as well as the experience of African students in the Eastern Bloc during the Cold War—was triggered by coming across a letter from Moscow in my family archives, sent by a family friend, who was a Rwandan studying near Moscow during that time. Both the period and this geographic encounter had also previously caught my attention, as several renowned filmmakers from the African continent had studied in the Soviet Union and carried home the renowned form of Soviet montage in their films—filmmakers Ousmane Sembene, Sarah Maldoror, and Abderrahmane Sissako, for example.

I started my research by exploring both the political and artistic interrelations in all the “layeredness” of the 1960s and 1970s, trying to gain an insight into the geopolitical dynamics of the Cold War, and their entanglements with the politics on the African continent after its many independences—taking particular interest in what the experience of individuals studying in the Soviet Union through a scholarship would be like. This research not only challenged my perceptions about that period in time—myself being of the generation that was raised after the fall of the Berlin Wall—but started to give me a deeper comprehension of this turbulent but also insightful period of society.

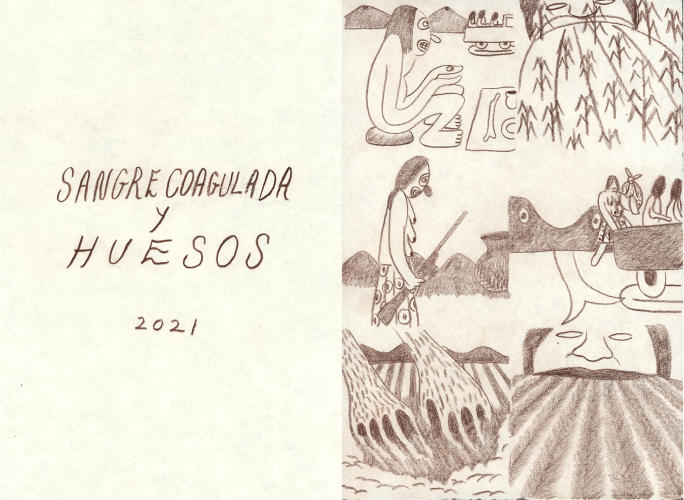

Little is known about the personal experiences of the African students, their personal lives, personal positioning, and negotiation with the communist ideology, nor their trajectories after their return to their homelands. Using a screenplay as a research method allows entry to this unknown space. Through the figures of Gilbert and Idrissa, the story’s protagonists, I want to explore the historical potentiality of two intersecting narratives: postcolonial and East European, as a refuge from a geopolitically constructed western reading of history. Being born in Rwanda, mostly raised in the west—in Belgium—has framed my perception of history, and by extension, my imagination and understanding around the Cold War and Eastern Europe. The experience of being perceived as a migrant enabled me to question and acknowledge the geopolitical ingredients in the imposed notions of history and, particularly, which histories are told. Therefore, I used counternarratives coming from more informal archives in the development of my research, such as oral histories and family archives.

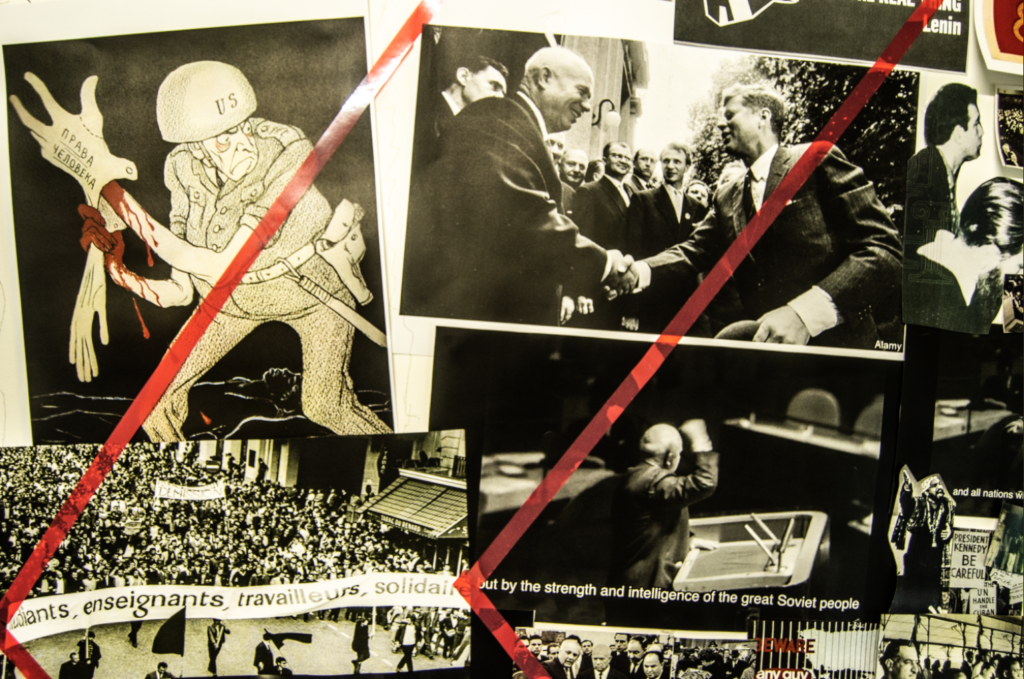

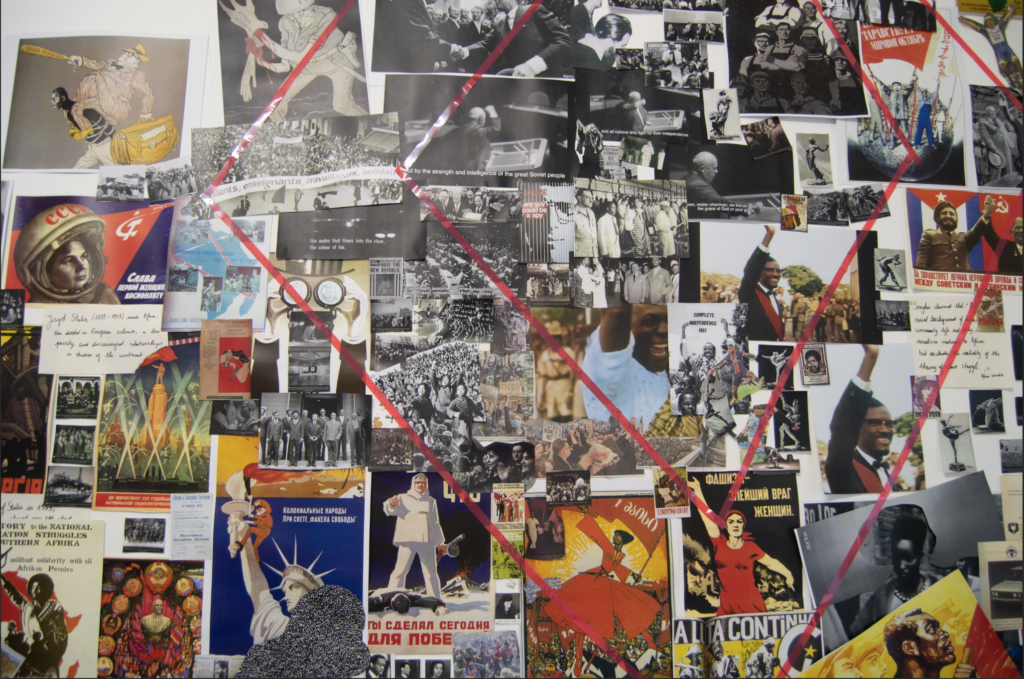

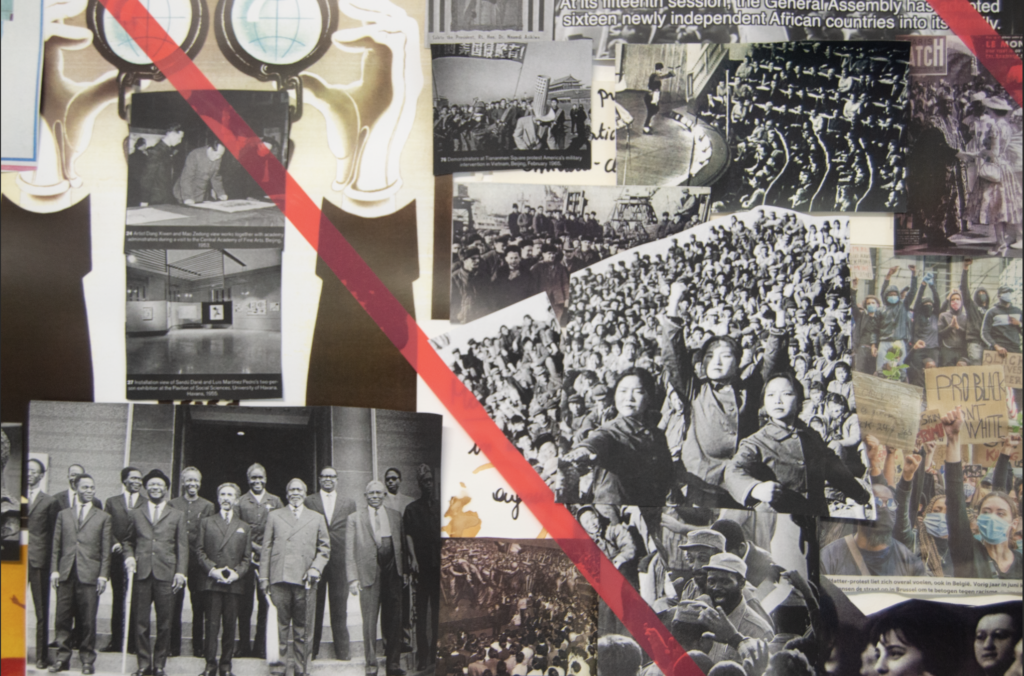

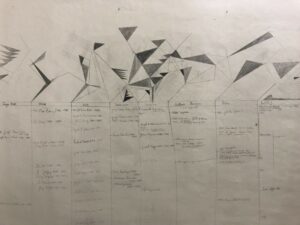

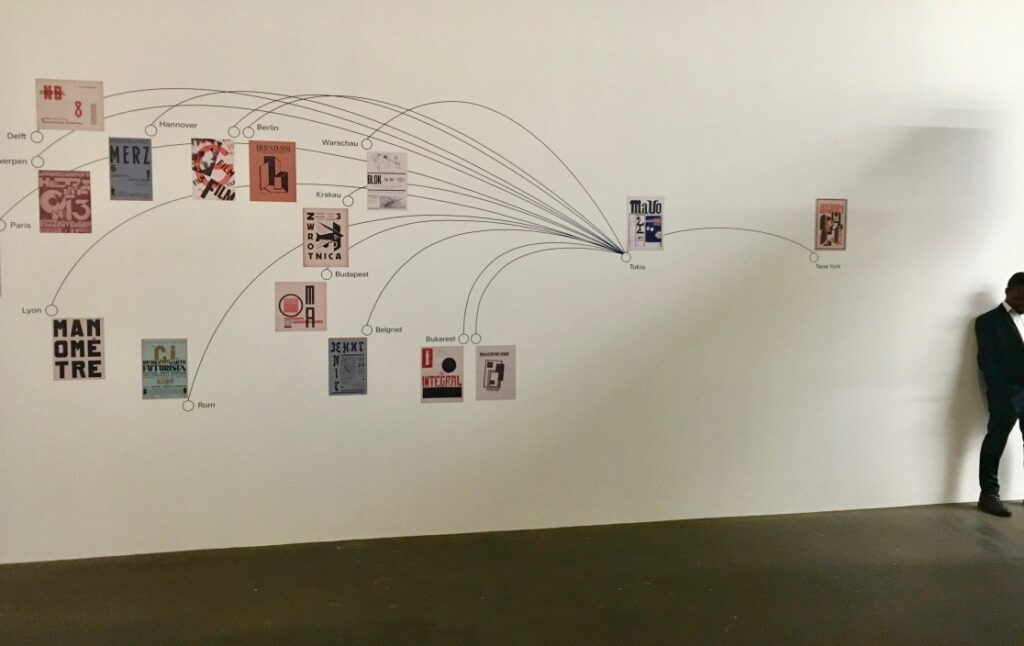

My research resulted in the performance of a written screenplay, surrounded by a mapping of historical images in my studio during my residency at Wiels, Centre for Contemporary Art, Brussels. The performance—and its projections and the misunderstandings that unfolded in the collage of historical images and personal dialogues—was an experimentation in rehearsing ways of engaging with oral knowledge beyond reproducing the violence inherent as much in the Cold War era as in the present world.[1]

Screenwriting as Artistic Research

Int. General Assembly United Nation. End of the afternoon.

12 October 1960

A Soviet man, small in stature, about 50 years old, walks up the steps nervously. He sits down in front of the microphone, looks at the assembly. His posture is straight. His arms are up. There is a silence. He looks down at his notes he took on a little paper. He sits down in front of the microphone, looks at the assembly with a confident air, opens his mouth and speaks.

Nikita Khrushchev

(with a tone of commitment)

I am glad to have this opportunity,

on behalf of the Soviet people,

to welcome the young independent

African states

which have recently

joined the United Nations

and to wish them prosperity

and success.

Our century is the century

for the struggle of freedom,

the century in which

nations are freeing themselves

from foreign domination.

The peoples aspire to a

dignified life

and are fighting for it.

Victory has already been

wining many countries and lands.

But we cannot rest on our laurels,

for we know that tens of millions

of human beings are still languishing

in colonial slavery and

suffer serious hardships.

The body of Nikita Khrushchnev becomes stiffer each word he utters. The tone in his voice is hard to define, it seems like something between anger and passion. Every word’s value is recognized by a very expressive and precise articulation.

We are in a period that we call

that of the great and promising

scientific discoveries.

We have designed the atomic bomb[2]

and we are penetrating

the mysteries of the

structure of proteins.

The extent of our knowledge

is a source of astonishment

even to ourselves.

Nikita Krushchev stops bends down, and disappears from our view. Restlessness in the company. Whispers occurs in a nervous tone. It’s like he vanished. He reappears with one of his shoes in his hand. The noise of his shoe gives a rhythm to the continuation of his speech.

*tap*

(Almost yelling)

*tap*

“This life, itself,

depends on the effective

power of the Pacific States,

and the support

of the overwhelming

majority of humanity.

Life cannot be reduced

to simple geometric rules,” [3]

“If, instead of plundering

and exploiting,

the metropolitan states.

If, instead of plundering

and exploiting,

the metropolitan states

had been truly guided

by the interests of the colonial people,

if they had really given

them the help they needed,

the people of the

colonies and metropolitan countries

would have developed uniformly.

Instead of presenting such striking

differences in the development

yes, in the development of

their economy, their culture and

their national prosperity.”

Nikita Krushchev looks at the assembly with an inquisitive gaze.

Look at what is happening

in the colonies.

Africa is bubbling and

bubbling like a volcano.

His voice replicates the voice of a bubbling volcano.

No one can dispute the fact that

the Soviet Union has spared no effort

to ensure the continuation

of this happy trend in the development

of international relations.

Nikita Krushchev looks at the assembly and takes a deep breath to continue his speech.

Int., Oval office, Washington D.C, United States, Night.

5 September 1961

A rather handsome white man of about 40 years old with brown-ish-blond hair, is sitting at his desk. He seems tired. The dark circles under his eyes are marked. He sips in a rhythmic manner from his whiskey. He takes the first from the stack of letters in the corner of his desk.

On the letter, written in elegance. ‘Letter to President John F. Kennedy from the Non-Aligned Movement’.

John F. Kennedy whispers out loud:

“We, the Heads of State and Government of our respective countries participating in the Conference of Non-Aligned Countries held in Belgrade from September 1 to 5, 1961, take the liberty of addressing Your Excellency on a matter of vital and immediate importance to all of us and to the whole world. We do so not only in our own name, but at the unanimous request of the conference and of our peoples.”

“We are distressed and deeply concerned at the deterioration of the international situation and at the prospect of war which now threatens mankind. Your Excellency has often emphasized the terrible nature of modern warfare and the use of nuclear weapons, which may well destroy humanity, and has pleaded for the maintenance of world peace.”

“… we urge the opening of direct negotiations between Your Excellency and the Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, who represent the two most powerful nations today and, in whose hands, lies the key to peace and war. We are convinced that, devoted as you both are to world peace, your efforts, through persistent negotiations, will lead to a breakthrough in the present impasse and will enable the world and humanity to work and live-in prosperity and peace.

We send this identical letter to Mr. Nikita Khrushchev, Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. “

The phone rings. Kennedy takes another prolonged sip from his glass of whiskey.

John F. Kennedy

(tiredly)

Yes, Yes …

…

I am coming…

Keep some food

for me

…

J.F. Kennedy

(exhaustedly exhales)

…

Yes, Yes, of course

…

I was finishing something

Yes of course, I am coming

Kennedy hangs up the phone. He takes a notebook and carefully notes the names of the officials who had signed the letter. While writing the names down, he reads them out loud and practices the pronunciation of their names.

Cyrille Adoula, Prime Minister of Congo and Minister of National Defense

Haile Selassie I, Emperor of Ethiopia

Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, President of the Republic of Ghana

Aden Abdulle Osman, President of the Republic of Somalia

El-Farik Ibrahim Abboud, Chairman of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces and Prime Minister of the Republic of Sudan

He closes the notebook. He caresses with his forefinger on the title of the book, which reads ‘African Statesmen,’ written on the cover with a red marker.

*

Ext., Square in front of a University, Voronej, Soviet Union. afternoon.

11 September 1972

A large, sleek building. White with yellow tones. The type of building that exudes authority and work ethic. In front of it, a snow-covered grassy plaza. Sound of steps crunching in the snow. A group of boys step up to the building. The first in the group has to use force to open the door.

*

Int., Eating Room in Dorm, Voronej, Soviet Union. Evening.

11 September 1972

The walls are decorated in two colors, red and white. The room looks empty and is filled with dinner tables. Two groups of students are sitting in both corners, at both ends of the room. In one corner sits sitting a group of Russian students and in the other corner sit two Black African students. One of the students eats with large spoons, the other looks at his plate somewhat doubtfully. The radio is on, a voice seems to read the latest news in Russian.

Gilbert

Idrissa! What’s the matter?

You have such a strange look

on your face.

Idrissa

It’s only the food that manages

to warm me up. It’s so cold.

Aren’t you cold?

Gilbert

What a joy, this snow!

It is so beautiful!

So white…

but so cold.

I’ve never seen

anything like it.

Idrissa

Winter has barely begun

and it is already -15°C.

Gilbert

You’ll get used to it!

Idrissa

Never!

Gilbert

By the way, What are your first

Impressions of the Soviets?

Idrissa

They’re all drunks…

and very funny!

they told me about it

I heard about the soviet humor.

but this… haha

had to laugh so hard

last night!

Gilbert

Ha ha!

I have a good impression.

I feel like they are nice.

Especially to foreigners.

Idrissa

The women by the way

some of them are a bit cold

and others are really interested

in the clothes that I wear,

the music I listen too

even the watch, I am wearing.

Like really obsessed

With everything that comes

from the outside.

Gilbert

You have to understand:

on the radio, on TV

In the newspapers,

they only talk about

The Soviet Union and

the socialist states…

It’s normal, isn’t it?

Wouldn’t you be interested what

comes from outside?

besides, there are some surprises, no?

Idrissa

Like what?

Gilbert

Well, contrary to what

I was told home.

There is freedom of worship here.

In theory, everyone practices as they wish.

Idrissa

Oh yes, didn’t you go

to church the other day?

Gilbert

But yes, when I talk to

the Soviets I see that

they have an atheist

upbringing from

a very young age.

But the contradiction:

the old people,

on the other hand, believe

in God and they even

attend church a lot.

When I was there,

they were all old people!

*

Backstory

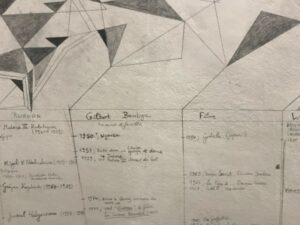

Gilbert Basebya:

Gilbert is born in 1952 in Rwanda. He’s the first born of a family of 6 children. He was 10 years old, when the Rwandan Independence was announced. Thanks to a family friend, he could attend the prestigious seminary school, a school owned by Belgian priests. All the scholarships to the United States where already given to students that were friends with the government. That was initially his choice. He passed by the Russian embassy, as they were known to give scholarships easily. It would be his way, to study abroad and come back with a degree, maybe pass by the West. If possible.

Int. Dining room. Dormitory. Voronezh. Soviet Union.Afternoon.

5 February 1973

Idrissa

(joyfully)

Ah Gilbert! Happy New Year!

Tell me how

the new year party was.

Gilbert

(excited)

Aha, all the Rwandans were

together with some friends.

It’s a good thing to study abroad:

This opportunity to meet students

from Vietnam, from D.R.A.,

Latin America, and Asia.

Idrissa

How was it?

Gilbert

We get to talk, for a long time.

And you know Idrissa, actually,

I’ve noticed that their problems

are not different from ours.

You realize that there are more

than 25 countries represented

in this university?

Idrissa

Yes, I met yesterday

For the first time

different Malagasy

and Nigerians.

By the way,

did the exams go well?

Gilbert

I am so proud of my fellow students:

They all passed their exams well.

We did not disappoint them!

They always have

a good impression of us!

Idrissa

I sense a real fear among

my Russian friends of losing

their scholarships.

Gilbert

The Soviets rate all the works

on 5 points, 5 = YB, 4=B, 3=AB, 2=M.

The Russian students normally

have a scholarship of 40 rubles,

when a student receives 5 points

during a year the scholarship

is increased to 100 rubles.

When a student receives 4,

he passes but his scholarship

is not increased.

If a student receives 3 points,

he passes, but does not receive

a scholarship and is kicked

out of the university residences.

Idrissa

Oh really?

This is intense, right?

Gilbert

So, all the Russian students

work a lot for fear

that their scholarship will be cut.

But I have to admit,

I think that such a system

can stimulate

the students’ work.

Here, everything is provided for

the students to study well.

Books cost almost nothing.

Books that cost 2000 francs at home

do not cost even one ruble here.

And every night there is a teacher

available for students.

Idrissa

Yeah, I see your point of view.

Let’s discuss this with other students,

And see what they think about it.

*

Backstory

Idrissa Kamara:

Idrissa was born in 1950 in Guinea-Bissau. When Idrissa arrived in the Soviet Union, Guinea-Bissau was still fighting for its independence from Portugal. That would last from 1963 to 1974. Guinea-Bissau in its independence war was, among others, backed by Cuba, the Soviet Union, Romania, and Yugoslavia. Idrissa ended up studying in the Soviet Union, due to a family friend. The family friend was a member of the communist party of Guinea Bissau, he could fix a scholarship to study abroad, in Russia, in the Soviet Union. Idrissa saw it as an opportunity to study abroad.

Int. Sleeping room. Dormitory. Voronezh. Soviet Union.Afternoon.

20 March 1973

Gilbert lies in bed, dressed and staring at the wall. Right in front of him, Idrissa, is sitting in a chair. They talk seriously.

Gilbert

(worried)

Idrissa, you’ve hardly

eaten at all.

What’s going on?

Idrissa

(in a cold tone)

Do you know who

Amìlcar Cabral is?

Gilbert

Yes, yes,

He wrote about

Marxism, didn’t he?

Such an interesting

and fascinating man.

I remember a quote from him,

which I liked,

I think it was:

“Christians go to the Vatican,

Muslims to Mecca

and the revolutionaries

to Algiers.”

Idrissa

I have some bad news:

I received a letter

from my mother

this morning.

…

She told me that

Amìlcar Cabral is dead.

He was killed. I don’t have

any more details, yet.

A silence of a few minutes, pain and anxiety are suddenly strongly felt in the room.

Gilbert

(in a serious tone)

This brings me back

to all the murders

following the independences:

Patrice Lumumba,

with his unpredicted speech,

Louis Rwagasore,

the immense bright mind,

and for Rwanda,

the king, Mwami Mutara III,

who mysteriously died,

in a hospital in Burundi,

after he started confronting

the Belgians.

This is exactly

why I didn’t want to study in Belgium.

Idrissa

You know Gilbert…

never forget…

that those powers that try

to “modernize” us,

or who supposedly

have the authority of “morality”,

are the ones who

created an atomic bomb. [4]

Can you imagine that

they used it?

So that’s when you realize.

When they talk about sauvages.

They actually talk about

Themselves.

Gilbert

It’s so scary,

All that.

Idrissa

You know, the fear of

a lot of my friends,

a lot of students,

was to be sent

to the Soviet Union.

Gilbert

Why is that?

Idrissa

First, they thought that in this country

the studies were too “easy”

and especially those who come back from here

were not looked at with the same

admiration as those who came back from

France, for instance.

The communist ideology, is and

was fashionable in the discussions,

but it ended up revolting some of us,

and we did not wish to go

to the country, which in our eyes,

had replaced the former colonial powers.

You know, that our leaders were

inspired by Soviet governance?

To the point of maintaining

the cult of personality typical of the USSR?

You know, Gilbert.

I think a lot about: what comes after this?

Going back.

I remember an uncle coming back with

a degree of the Patrice Lumumba University.

But you know, a degree from the

Sorbonne is way more respected.

Gilbert

(worried)

I think about it a lot, too.

About my life after this…

Hope it was all worth it!

5 Years Later

Int., Sleeping room, Odessa, Ukranian USSR. Evening.

5 May 1977

Gilbert is sitting at his desk, pencil in hand, drawing a plan of action on a blank sheet of paper. Idrissa knocks on the door and enters in the room. Gilbert ignores him and keeps on writing.

Idrissa

What the hell are you doing?

Gilbert

We, the Rwandan students,

are preparing a big strike.

Idrissa

But, why? Are you sure?

This can be dangerous.

Gilbert

We have been asking

a long time for

the Rwandan government

to grant us

holidays back home,

but so far,

the government

has been silent…

I don’t know

if you understand,

how we live in

difficult situations.

Spending six years in the USSR

without returning home!

Can you imagine?

Idrissa

But it’s difficult

for everyone?

Your compatriots?

What do they think?

Gilbert

But everyone agrees!

It’s very difficult to handle,

and many people

become mentally deranged.

Idrissa

But what are you going to do?

Gilbert

We are thinking of going

on a general strike

until our demands are met.

Idrissa

But how are you organizing this?

Gilbert

Across the whole territory of the USSR

Rwandan students have held

meetings to study

how the strike would be conducted.

Idrissa

But the Soviet authorities,

how will they react?

Gilbert

I don’t know. We’ll see.

Int. Dining room. Odessa, Ukranian USSR. Evening.

25 April 1977

Idrissa and Gilbert are sitting silently in the corner of the dining room. They both look a little stressed. They have trouble eating the food on their plates. They speak very silently. The conversation is hard to understand.

Idrissa

(in a nervous tone)

I have to tell you something, Gilbert.

I’ve been talking about your strike plans

with a good friend of mine.

Gilbert

I asked you to be discrete

about this!

Idrissa

I mentioned it to James,

that Ghanaian student.

You know him,

he’s trustworthy!

He said something

That might interest you

Gilbert

What did he say?

Idrissa

That about 15 years ago, a group of

Ghanaian students went on strike to address

the mysterious death of one

of their fellow students.

He was found dead in the snow

some weeks before his wedding

to a Russian girl.

Gilbert

What a horrible story!

How did the Soviet react to this strike?

Idrissa

That’s what I wanted to speak to you about

…

At that moment it was Krushchev,

the head of state.

He reacted really vividly.

He declared that Africans could dance on

their heads at home, but that

they would not allow demonstrations again

in the USSR

Can you imagine?

He then offered exit visas to those students

who didn’t like the treatment

they are receiving here.

Just, be careful

Gilbert…

Is this worth it?

Gilbert

(calmly)

Thank you for letting me know this.

But I can’t let fear run my life anymore.

Int. At a party in a bar, Odessa, Ukranian USSR. Night.

15 June 1977

A pub with sparse lighting, very quiet classical music in the background. The sound of bottles on the tables make the music almost inaudible. Several groups of men are in the pub. Idrissa and Gilbert are sitting in a dark corner. A half empty bottle is between them on the table.

Idrissa

So how did it go

with your ideas to invade

the Rwandan embassy?

Gilbert

Look, our plans were aborted.

The authorities noticed

the uneasiness which reigned among us,

and to stop any enterprise

of the students

against the embassy of Rwanda,

armed militiamen were placed.

It became impossible to do anything

against the embassy and in our plans,

the last measure was to invade the embassy

and drive out the ambassador.

Idrissa

But what did you do?

Gilbert

We decided to take the legal route,

and asked the Soviet

Ministry of Public Education

permission to send a

delegation to the embassy.

The delegation was received by

the ambassador, who answered that

he had not received any order from Kigali and that our requests were still under consideration.

The delegation returned unsatisfied

And we started the strike.

The Rwandan students refused

to attend classes until

their demands were met.

Idrissa

But how did the Soviets react?

Gilbert

They threatened to expel

all the leaders of our organization

if we didn’t calm down.

So, on the request of

the central committee,

we stopped the strike.

But this story is not over,

Idrissa.

We decided to start it again

if the Rwandan government

continues to keep silent.

Idrissa and Gilbert order one last drink for the road.

*

[1] I would like to thank Anna Smolak, independent curator, for giving me the opportunity to perform this screenplay as part of the program Lectures on the Weather in Snagov, Romania, and through conversations helping me to find the words to explain what the experiment was about.

[2] The performers pronounce the word together.

[3] This is a term that was suggested by an automatic translation. Although this may seem like an incorrect translation, I chose to keep this term. As it is an interesting lapsus for what is actually meant.

[4] The performers pronounce the word together.

Bibliography

Julie Hessler, ”Death of an African Student in Moscow”, Cahiers du monde russe 24, no. 1–2 (2006).

Constantin Katsakioris, “Transgresser les frontières de la Guerre froide. Militants, intellectuels et étudiants africains en Union soviétique, 1956-1991,” Présence Africaine, Nouvelle série, 175/176/177, (2007/2008).

Mark Nash, Red Africa: Affective Communities and the Cold War, (London: Black Dog Press, 2016).

Jean-José Maboungou, “Voyage en Brejnevie: Vie ‘Rêvée’ des étudiants du Tiers-monde en Russie soviétique ,” Cahiers d’études africaines 226, (2017).

Maxim Matusevich, “Journeys of Hope: African Diaspora and the Soviet Society,” The African Diaspora 1 (2008), pp. 53–85.

;)

;)

;)