No Linear Fucking Time

“Dates die fast,” Raphaël told me. “We don’t care much about their temporary logic. Dates can be like the lines of hopscotch—we can jump around between them. The thing they are useful for is this: discovering the hidden order. After that they vanish. The important date is the one coming.”

But order too wears away and goes. We’re never done with our outrageous ancestors, comic paladins, lost in the savannas where we forgot them. The present endlessly increases with their defused words. Your head is overloaded with them. You fall into the maelström.

—Édouard Glissant, Mahagony

The titular tree in Édouard Glissant’s novel Mahagony (1987) stands as a witness to centuries of anticolonial struggle and survival in the Martiniquan landscape. Offering shelter to maroons and becoming an arboreal record-keeper for collective memory, the ancient tree tells stories that move back and forth over hundreds of years. A basic chronological outline is offered at the start of the novel, and there are recurrent dates throughout the narrative which relate to the colonial history of Martinique, but as the character Raphaël observes in the passage above, dates “can be like the lines of hopscotch—we can jump around between them.” The story told here is ultimately one that can only be told through the undoing of chronological order; the mahogany tree is part of an ancestrally imbued landscape, where relations forged across long durations come to sense what Glissant describes as “the mutter of time that rumbled over the land.”[1]

This focus of Prospections similarly engages a multitude of temporal registers through shifting scales and rhythms. As an integral part of the exhibition and discursive project No Linear Fucking Time (2021–2022), the impetus is grounded on an apprehension that presently dominating constructions of time—as an abstracted linear flow that runs autonomously and ineffably—promote a worldview that is ultimately world-destructive, and is desperately in need of reexamination. Throughout this Prospections focus and the broader project, various temporal ontologies are woven together. These include understandings of extra-corporeal and non-normative durations, ancestral presents and pan-temporal solidarities, and practices of reclaiming time through embodiments of slowness and interruption.

In the essay “Reclaiming Time: On Blackness and Landscape” (first published in PN Review in 2021), poet and writer Jason Allen-Paisant recounts that before he had started writing poems about trees (his collection Thinking With Trees was published in 2021), he had been busy “writing poems about the police and white cops killing Black people and black anger and rage and that kind of stuff.” While acknowledging the ongoing necessity of writing in reaction to racial violence, Allen-Paisant describes his more recent work as an expression in “reclaiming time.” Thinking about colonial history and antiblackness in terms of severed ties with the landscape and “the robbery of time from Black life,” he describes how poetry can offer a practice of slowness and a deepening of time, through which new forms of connectedness—amongst and beyond humans—become possible.

Allen-Paisant’s poem “Right Now I’m Standing” (an excerpt from which appears within the “Reclaiming Time” essay), centers on the remains of a tree in a woodland clearing, where the trunk is split open and partly rotting away, but new green leaves and other forms of life are also emerging out of it. “The raspberries feed on its breath,” he observes, “and beetles thrive in the slurry middle / where the bole rots.”[2] This co-existence of a plurality of temporal scales and directions is something that can only be sensed through practices of stopping and slowly observing—practices which Allen-Paisant insists on throughout this poem. “Though people / look suspiciously,” he writes, “stand and listen do not go anywhere.” “Right Now I’m Standing” ends with these lines:

We have been property

When I talk about reclaiming time

I’m just thinking about my body

standing in the middle of this woodland

and

doing nothing nothing

“Living the Not-Yet,” a conversation with writer and activist Walidah Imarisha, (first published in Toward the Not Yet: Art as Public Practice (2021)), also deals with forms of “reclaiming time,” by actively envisioning other possible worlds within this one. Drawing from her work as a prison abolitionist, and speaking specifically to movements and ideas led by Black struggle in the United States, Imarisha presses on the importance of being able to sense “this immense, pulsating, moving thread of liberation that wraps around itself and curls and flows.” Characterizing the construct of linear time as a “method of social control,” she calls for modes of “decolonized subversive time travel” which can take up the “liberation dreams of our ancestors” and “pull the future into the present.”

Also originally published in Toward the Not-Yet, critical theorist and filmmaker Elizabeth A. Povinelli’s “In Some Places, the Not-Yet has Long Been Already” reflects on the notion that many, including Povinelli’s collaborators in Karrabing Film Collective, have been witnessing the “catastrophe of the present” for ages. While liberalism’s hopeful orientation toward the horizon is troubled by the coming catastrophes of climate collapse, Povinelli writes from an understanding that the horizon of futurity has not been so brightly lit with possibility and promise for everyone. The ancestral catastrophes of coloniality and enslavement operate in a very different temporal order. “Ancestral catastrophes are past and present,” Povinelli writes, “they keep arriving out of the ground that colonialism and racism tilled, rather than emerging over the horizon of liberal progress.”

Reclamations of time, geared toward community and temporally “local” orientations, animate an interview with artists and activists Black Quantum Futurism (Rasheedah Phillips and Camae Ayewa), who draw from Afrofuturism, quantum physics, and “Afrodiasporic traditions of space and time that are not locked into a calendar’s date or a clock’s time.”[3] As discussed in the interview—another text which was first published in Toward the Not-Yet—BQF’s recent and forthcoming projects directly challenge imperial and colonial standardizations of time, particularly in relation to the International Prime Meridian Conference in 1884.

“Iridescent Ammunitions: Time Travel as Survival” is a new essay by artist, writer, and time travel practitioner Promona Sengupta, also known as Captain Pro of the interspecies intergalactic FLINTAQ+ crew of the Spaceship Beben. Grappling with the imposed linearity of timespace as a fundamental feature of colonial violence, the essay proposes a mode of time travel that is “untethered from colonial imaginations of the traversability of time and space.” While coloniality has enforced an externalization of time and space as things outside the body—expelling them “from subjective, situated knowledges, to rationed, regimented arrangements”—Captain Pro affirms practices of relational care and survival that restore time and space as embodied realities, “as things that are inside us and in relation to the world in which we are situated.”

Recent works by artist and musician JJJJJerome Ellis have also been concerned with “reclaiming time” back from its hegemonic governance. Here, we are republishing three parts of Ellis’s multi-faceted project The Clearing, including the original 2020 essay “The Clearing: Music, Dysfluency, Blackness, and Time,” which first appeared in the Journal of Interdisciplinary Voice Studies. Critiquing the exploitative and ableist temporalities of homogenized speed and efficiency, Ellis’s project engages with Blackness, music, and verbal dysfluency—including stuttering and other forms of non-normative speech—as “forces that open time.”

In “Melismatic Palimpsest”—an excerpt from Ellis’s book The Clearing, published by Wendy’s Subway in 2021—he asks how fluency is secured by dysfluency. “The two terms seem to suggest that fluency is the norm, and dysfluency deviates from the norm,” he observes. “But what if fluency were called dysdysfluency? How could we suggest that fluency is a narrowing of the fullness of dysfluency? What if dysfluency were called parafluency, a parallel flow, an alternate flow, a flow that ends up going in a different direction, to another country, only accessible via babbling brook?”

While syllabic singing attaches each syllable with a single note, the melismatic song distends the syllable through multiple notes (as in the “Aa-aa’’ at the start of Amazing Grace). In thinking about the kinds of attentive gathering that can be facilitated by the suspended and elongated syllable, Ellis turns to a live recording of Aretha Franklin singing Amazing Grace in 1972.[4] “She takes a hymn she knows most people in the church will know and makes clearings all through it,” Ellis writes. “She reminds us that a syllable is an opportunity for tarrying, for dilation, for divergence, for abundance. This is a rebuttal to “time is money:” Aretha and the congregation gather their wealth around them in the ample time she takes for the hymn. Hymn as a palace where everyone has a room.”

Also published in this NLFT focus on Prospections is “Together in Time,” a new interview with the theorist of queer temporalities Elizabeth Freeman. In conversation with NLFT co-editor Amelia Groom, Freeman talks about her concepts of “temporal drag,” “chrononormativity,” and “erotohistoriography,” and reflects on her own experiences of “crip time.” Through a discussion of recent video works by the artist duo Pauline Boudry / Renate Lorenz—whose installation (No) Time (2020) is included in the exhibition No Linear Fucking Time—Groom and Freeman also talk about dance, rhythm, and modes of embodied synchrony that exceed normative temporalities.

Freeman and Groom also discuss “Rhythm Travel” (1995), a short Afrofuturist story by writer Amiri Baraka, which we are republishing here on Prospections. The story is told through an encounter with an unnamed time traveller, or “rhythm traveller,” who has found a way to move across time by becoming music. “I turned into some Sun Ra and hung out inside gravity,” the traveler recounts. They also travel back in time to the unrepaired past, imbuing themselves into the music on a plantation in the antebellum South: “I seen some brothers and sisters digging a well. They were singing this and I begin to echo. A big hollow echo, a sorta blue shattering echo. The Bloods got to smilin because it made them feel good, and that’s the way they heard it anyway. But the overseers and plantation masters winced at that. They’d turn their heads sharply back and forth, looking behind them and at the slaves. Man, the stuff I seen!”

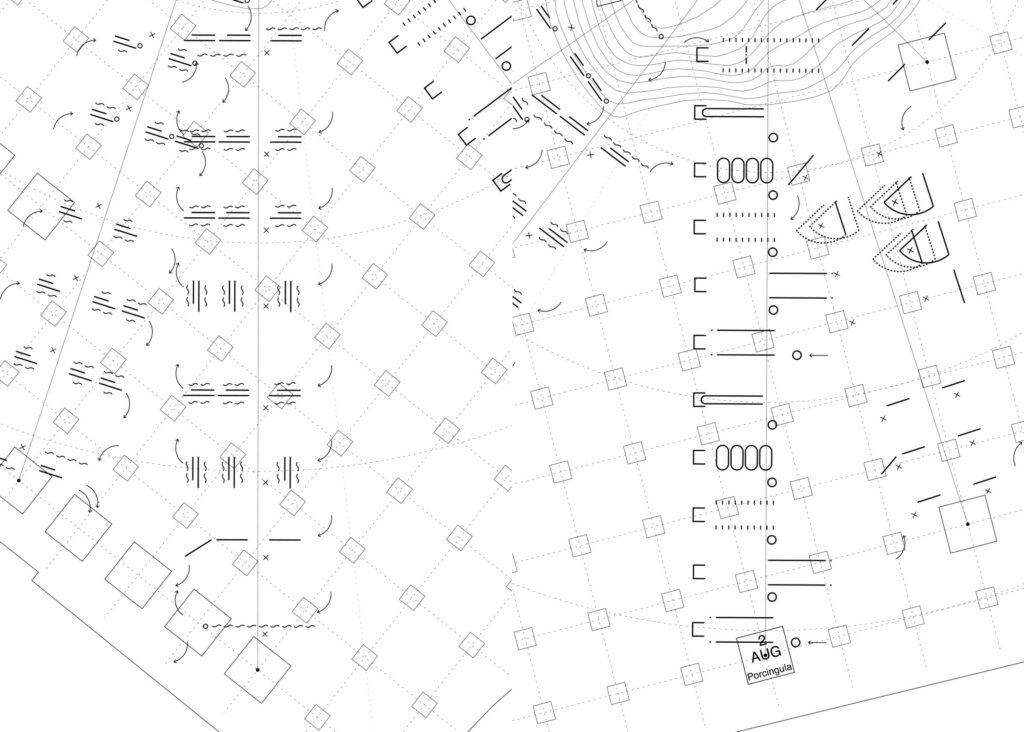

A specific claim to non-universalized temporal representation is encountered in the drawing Hemish Spiritual Pathway (2019), a detail of which appears in architect and researcher Nina Valerie Kolowratnik’s contribution “Secret Proof.” Made in collaboration with members of the Pueblo of Jemez in the American Southwest, the drawing represents the ceremonial dances that structure the traditional Hemish calendar year through moments of connection between the Pueblo and the ancestral spirits. As Kolowratnik points out in her accompanying text, the temporality of ancestral spirit relations cannot be captured in a standardized Western model of linear time. The lack of specific dates or time-frames in the drawing also relates to the fact that all of the ceremonial dances—except for two—are closed to the public, and the days on which they are performed remain undisclosed to non-Pueblo outsiders. Hemish Spiritual Pathway was first published in Kolowratnik’s book The Language of Secret Proof (Sternberg Press, 2020), which challenges the current US legal frameworks that define and demand “reliable” evidence from Indigenous communities—who want to reclaim and protect their ancestral lands without being forced to destroy their structures of cultural secrecy.

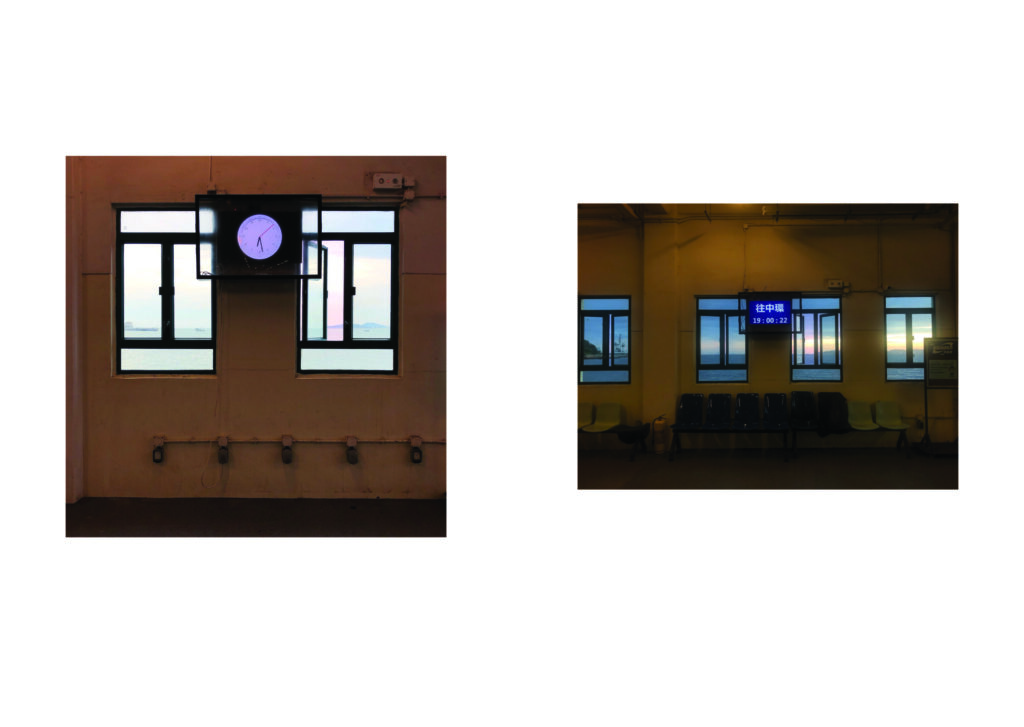

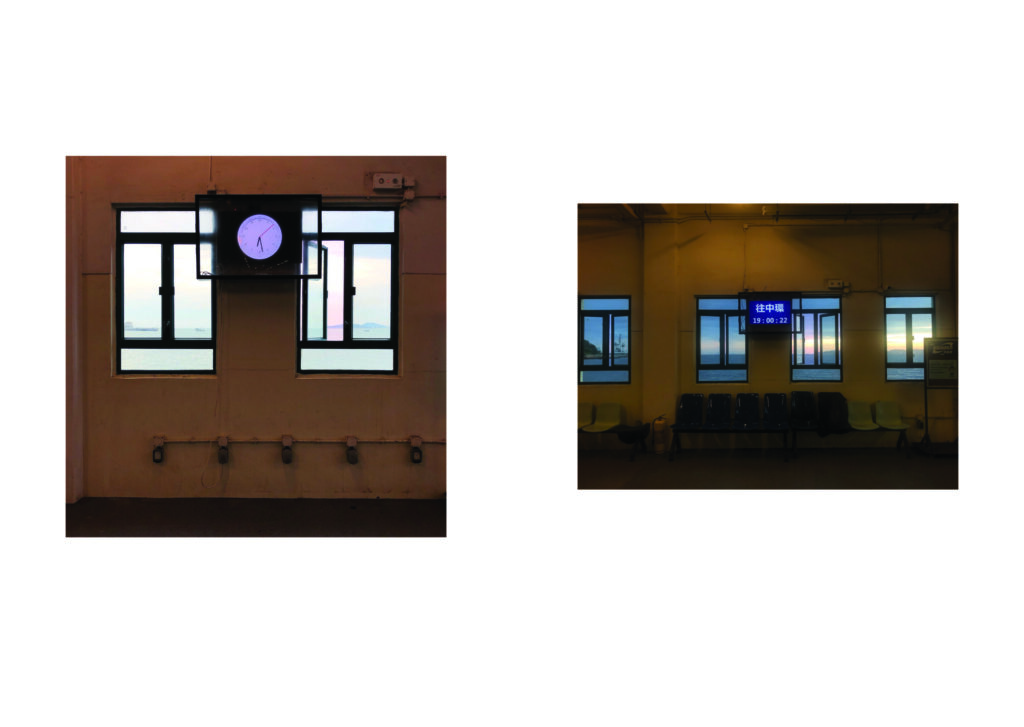

Several contributions also grapple with modern technological forms of linear measurement and social control. In the chapbook “Weird Times” (first published by The Douglas Hyde Gallery in 2021), artist and filmmaker Tiffany Sia offers a compressed history of time-keeping technologies in colonialist expansion, capitalist production, and warfare. Insisting that “lived time counters numeric order,” Sia proposes that perception could become calibrated towards the complex counter–tempos of the body. Alongside Sia’s text, “Weird Times” features a series of images selected by Yuri Pattison, who is one of the artists showing work in the No Linear Fucking Time exhibition. Sia and Pattison’s related video work SEA – SHIPPING – SUN (2021) was shot over a two-year period, but compressed to suggest it takes place over a single day. The video is set against a soundtrack of shipping forecasts from archival BBC Radio 4 broadcasts that served sailors and trade before the advent of GPS.

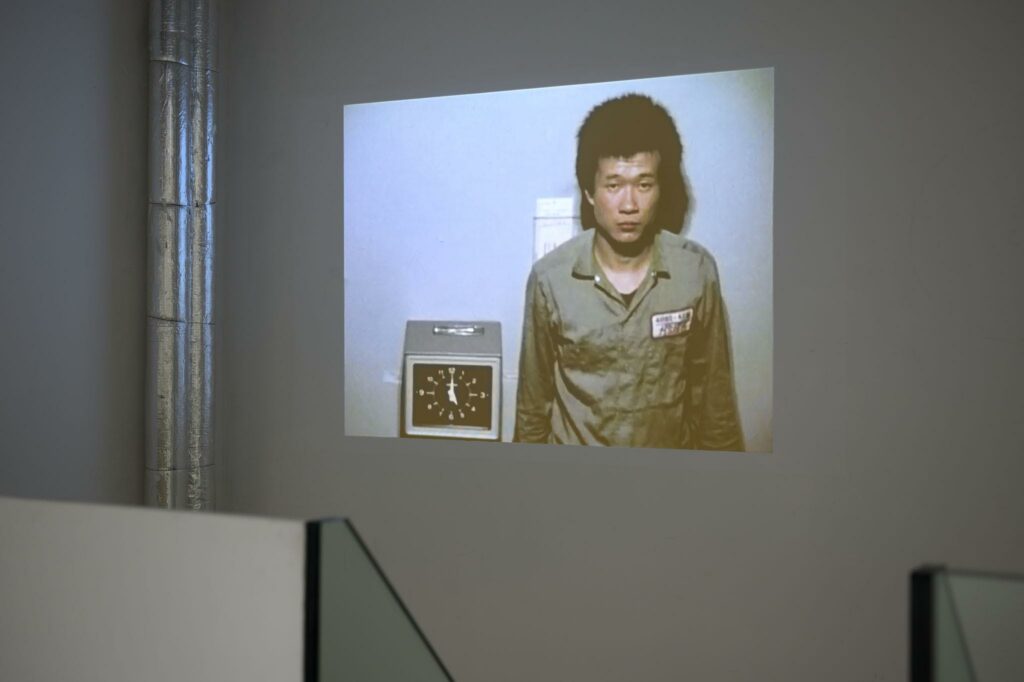

On display in the No Linear Fucking Time exhibition at BAK is Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performance 1980–1981: Time Clock Piece (1980–1981), a six-minute video that documents the artist’s durational performance of punching a time-clock every hour, on the hour, for an entire year. In her new essay “What a way to make a living,” Amelia Groom positions Hsieh’s piece alongside Dolly Parton’s contemporaneous antiwork anthem 9 to 5 (1980). Bringing this odd pairing into the present, Groom reflects on historical shifts in the ways that workers have been and continue to be exploited through techniques of time discipline. This Prospections focus also includes video documentation of “Observing Time,” an online conversation between Groom, Hsieh, and writer and curator Adrian Heathfield, held as part of BAK’s public program on 20 January 2022. Through reflections on Time Clock Piece and the artist’s other performances, the conversation moves through questions pertaining to time-keeping, durational aesthetics, and “dropping out” of art.

Also concerned with labor time and antiwork politics is Sam Keogh’s contribution Pig Eater, which features the script to a monologue which was first performed as part of the artist’s installation Sated Soldier, Sated Peasant, Sated Scribe (2021). Accompanying the text are details of collage elements from the installation, with drawings of flowers and worried cartoon clocks layered onto the image of a Microsoft Teams calendar with all the days cut out. Defunctionalized as a system for standardized time-keeping and bureaucratic scheduling, the calendar—taken apart and riddled with holes—can be repurposed for other means; Keogh’s character in the monologue tells us that he will use the cut-out days to construct a shelter to sleep under, and with the rest of the calendar he might make a trellis for the flowers.

The flowers, we learn, were all drawn during obligatory online work meetings on Microsoft Teams. “It looked like I was taking notes,” Keogh relates, “but I wasn’t. I was drawing pretty flowers on thin layout paper.” This reclaiming of time from inside a guise of worker obedience recalls cultural critic Michel de Certeau’s concept of “the wig,” from the French la perruque, where an employee is officially “at work,” but disguising their own work as work for their employer—de Certeau uses the example of a secretary writing a love letter while on “company time.”[5]

The floral motif throughout Keogh’s collages also relates to the artist’s interest in the famous medieval Flemish tapestries The Lady and The Unicorn (c. 1500, unknown artists) and their millefleur (“thousand flowers”) backgrounds, where many different kinds of plants and flowers are shown in simultaneous bloom. With seasonal fruits and flowers that would normally arrive at different times of the year shown all together, these backgrounds offer an image of anachronistic, temporally illogical abundance. Keogh fantasizes that after following the designs that were set for the foregrounds of the pictures, the tapestry weavers were able to improvise their millefleur fields, reimagining time beyond productive efficiency and disciplinary linearity, and encoding secret messages for the future:

. . . their detailing could slow the work of the weaver to their own pace, using the flowers’ beauty as an alibi for a less strenuous production process, and this might have been a kind of premodern sabotage, siphoning as much time and money and silk out of the aristocrats who commissioned the work in the first place, to make beautiful surfaces of impossible plenty, whose emancipatory message would fly over . . . no . . . under the heads of the rich and powerful and be legible only to the dispossessed of the future.

Another common thread in NLFT Prospections is an attunement to non-anthropocentric temporalities. Two commissioned creative essays focus on entities that are entwined in human existence while exceeding the temporal confines of present corporeal lifespans. In “Dearest Xen (Letters to Lichen)”, artist and scientist Adriana Knouf looks to lichen—which are composite symbionts of fungi and algae or cyanobacteria—as intimate partners in future collaboration. Through the lenses of “xenology” (Knouf’s term for the study, analysis, and development of the strange, alien, and other) and trans temporalities, she explores ways of learning from, and ecstatically participating in, cross-organismic intimacies and exchanges. Poet and writer Marianne Shaneen’s “Immortals: on the Ancient Future Lives of Stone and Plastic” compares stone and plastic, two very different substances which both exceed and intertwine with biological life. These substances are fascinating examples of material duration and symbiosis––one that has undergirded all Earthly life from the beginning, the other that is increasingly affecting planetary existence day by day. In an essay that blends epic lengths of time with dystopian presents and new materialist futures, stone and plastic come together as fellow travellers through alternate temporal ontologies.

Finally (for now), as an additional contribution and complement to the research in the overall project, we offer a bibliography which includes many of the research materials we consulted for the project over the past years of planning. The document has been compiled by researcher Natasha Matteson, who assisted and consulted on the project in several stages. In order to make it more useful and actionable, keywords are added to the selections, as are relevant links where available. The constellation of research around the politics of time is ever expanding, and we are always adapting our understandings of the fields and ideas it reaches toward. As such, we want to continue adding to this resource over the course of the project and beyond.

We would like to express our deepest admiration and appreciation to all these contributors, for their efforts in fucking with this world’s oppressive regimes of temporal extraction, deprivation, and subjection—and for assembling here in these virtual pages.

— Rachael Rakes and Amelia Groom, updated April 2022

[1] Édouard Glissant, Mahagony, trans. Betsy Wing, (1987, repr., Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2021), p. 6.

[2] Jason Allen-Paisant, “Right Now I’m Standing,” Thinking With Trees (Manchester: Carcenet Press, 2021), pp. 38–39.

[3] Black Quantum Futurism (Camae Ayewa and Rasheedah Phillips), Rachael Rakes, and Jeanne van Heeswijk “Practical Futurism and the Local Otherwise,” in van Heeswijk, Hlavajova, and Rakes, eds., Toward the Not-Yet, p. 81.

[4] Aretha Franklin, “Amazing Grace (Live at New Temple Missionary Baptist Church, 1972),” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CBKwV6oNYvw.

[5] Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life, trans. Steven F. Rendall (1984, repr. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1998), p. 25.

COLOPHON

Editors: Amelia Groom and Rachael Rakes

Managing Editor: Wietske Maas

Copyediting: Aidan Wall

Proofreading: Wietske Maas and Aidan Wall

Editorial Assistance: Natasha Matteson and Lou Rosenkranz

Translation (English to Dutch): Julia Alting, Kai Bijnen, and Olga Leonhard

Graphic Design: LeftLoft and Sean van den Steenhoven for LeftLoft

Website Support: Babak Fakhamzadeh

Editorial Board: Maria Hlavajova, Wietske Maas, and Rachael Rakes

;)

;)

;)

;)

;)