Online Screening of Oleksiy Radynski’s Landslide and Interview with Grant Watson

BAK 2019/2020 Fellow Oleksiy Radynski’s film Landslide (2016) premieres online 26 August 2020 as part of the screening series From Matter to Data: Ecology of Infrastructures, 29 July–9 September 2020, Museum of Modern Art, New York. This series presents a selection of 15 films and video works available in three part. Radynski’s film is part of the third screening “Past’s Futures: Anthropocene or Capitalocene?”, screened from 26 August until 9 September 2020. Read more about the screening series at MoMA’s screening platform post here.

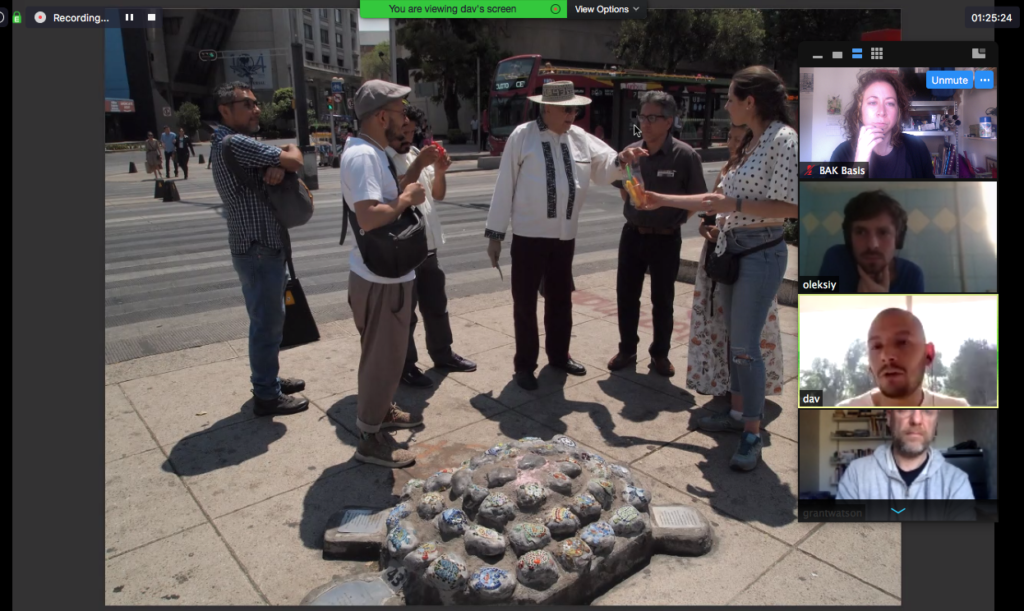

As part of his Fellowship research trajectory and project How We Behave, BAK 2019/2020 Fellow Grant Watson interviewed the Fellows about resistance and political practices. Radynski spoke about Landslide. Read some of the interview below! This interview will be part of the culmination of the Fellowship program Propositions #12: Waves Breaking Walls, Futures in Movement taking place 12 September 2020.

Grant Watson: Tell me about the place where Landslide was shot.

Oleksiy Radynski: Several years ago, there was a situation where my collective and other collectives and artists occupied a piece of land in central Kiev that had been abandoned because of a natural and social disaster in the 1990s. This abandoned area gradually emerged as a refuge, or last resort, for a lot of counter cultural artists. We’ve been running a small space in a garage coop, basically a cluster of workshops and DIY studios. It was completely fluid, completely makeshift, and not a very comfortable situation, but it seemed to me that there were some constellations of really interesting artists and practitioners there, who did things in the same place at the same period of time. So, it was interesting for me to document it, to make people discuss their work on camera and argue about things we’ve been arguing about for quite some time.

This was this situation of an ephemeral queer existence of several avant-garde personalities, which I decided to capture this with a film. By making the work, I thought I would kind of claim that this was something that actually exists, and that’s something others maybe have to remember. Otherwise it would completely evaporate. So, in a way the film almost faked this phenomenon, or this artistic situation, or this artistic cluster, because that is what films do in most cases. On film things look more interesting than they are in life, for better or worse. So, this was an experiment in making things real by fictionalizing them a little bit, or by manipulating them—things that maybe wouldn’t be real otherwise.

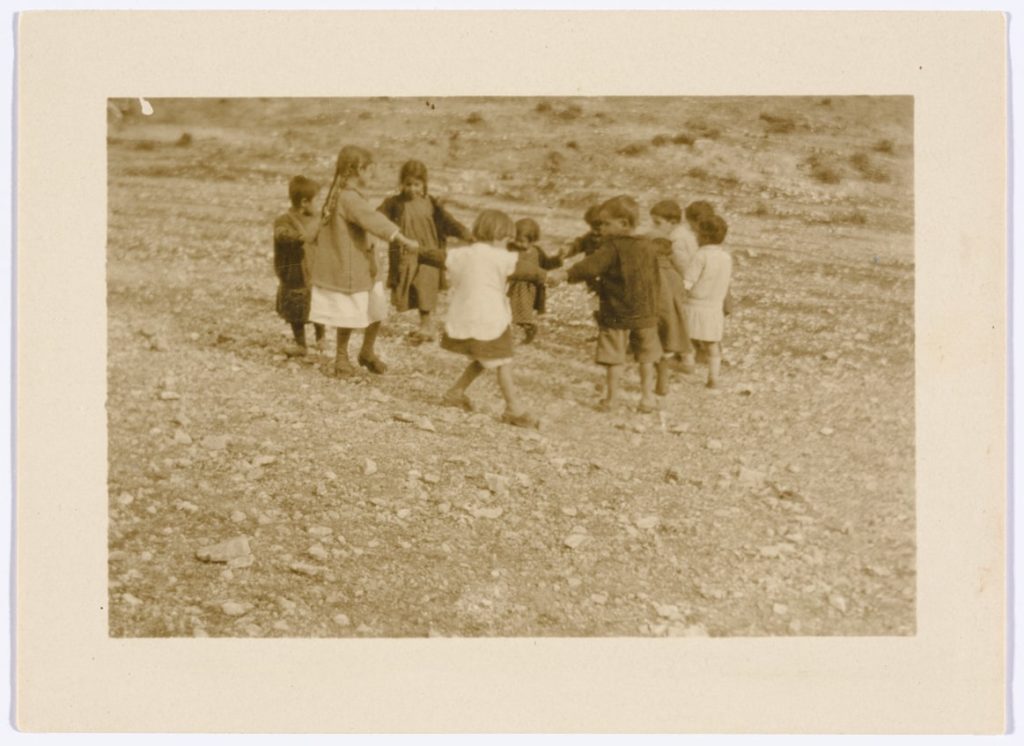

Taking over this territory in the city center was like the return of the humans to an area that was taken from them by the forces of nature and of social destruction. In the 1990s, there was a kind of small-scale apocalypse, a geological disaster, a landslide, in this area—and since then it has been uninhabited, abandoned. A whole street of 19th century bourgeois buildings that ceased to exist in the 90s because the state structures collapsed, and social structures collapsed. Nature, as we now know, restores itself very quickly in these situations. In the course of ten years there was just a wood there and then humans started to return to this area that they were kicked out from, and the first to come were artists, as sometimes happens.

GW: What was your relation to the characters of Landslide prior to filming?

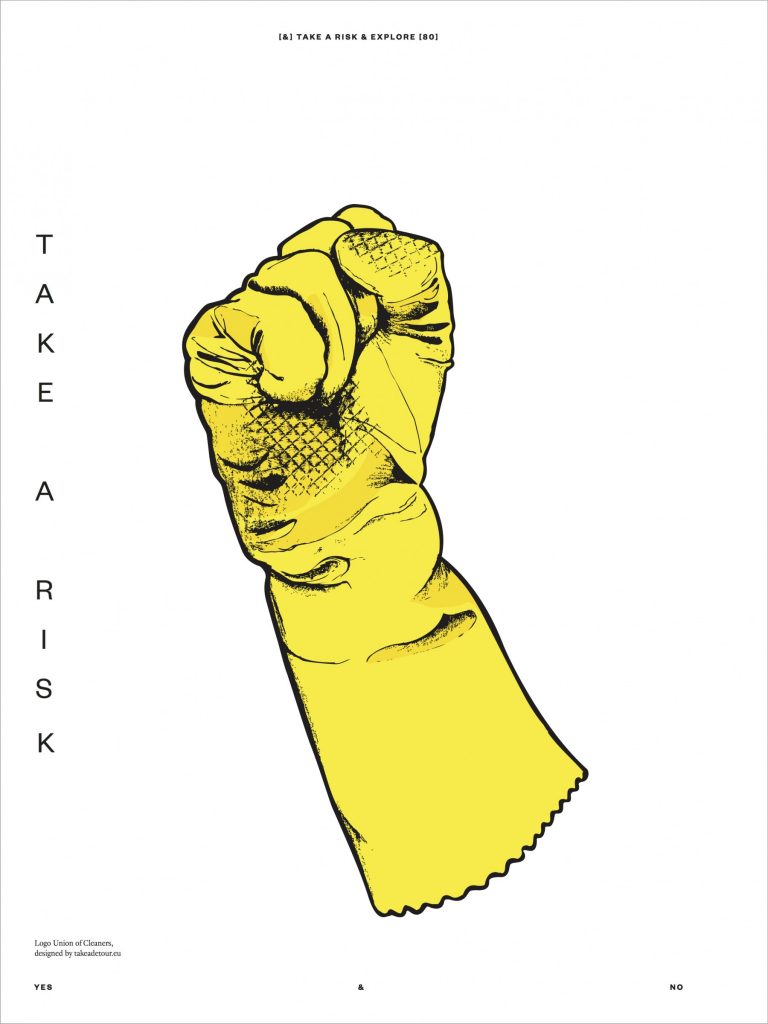

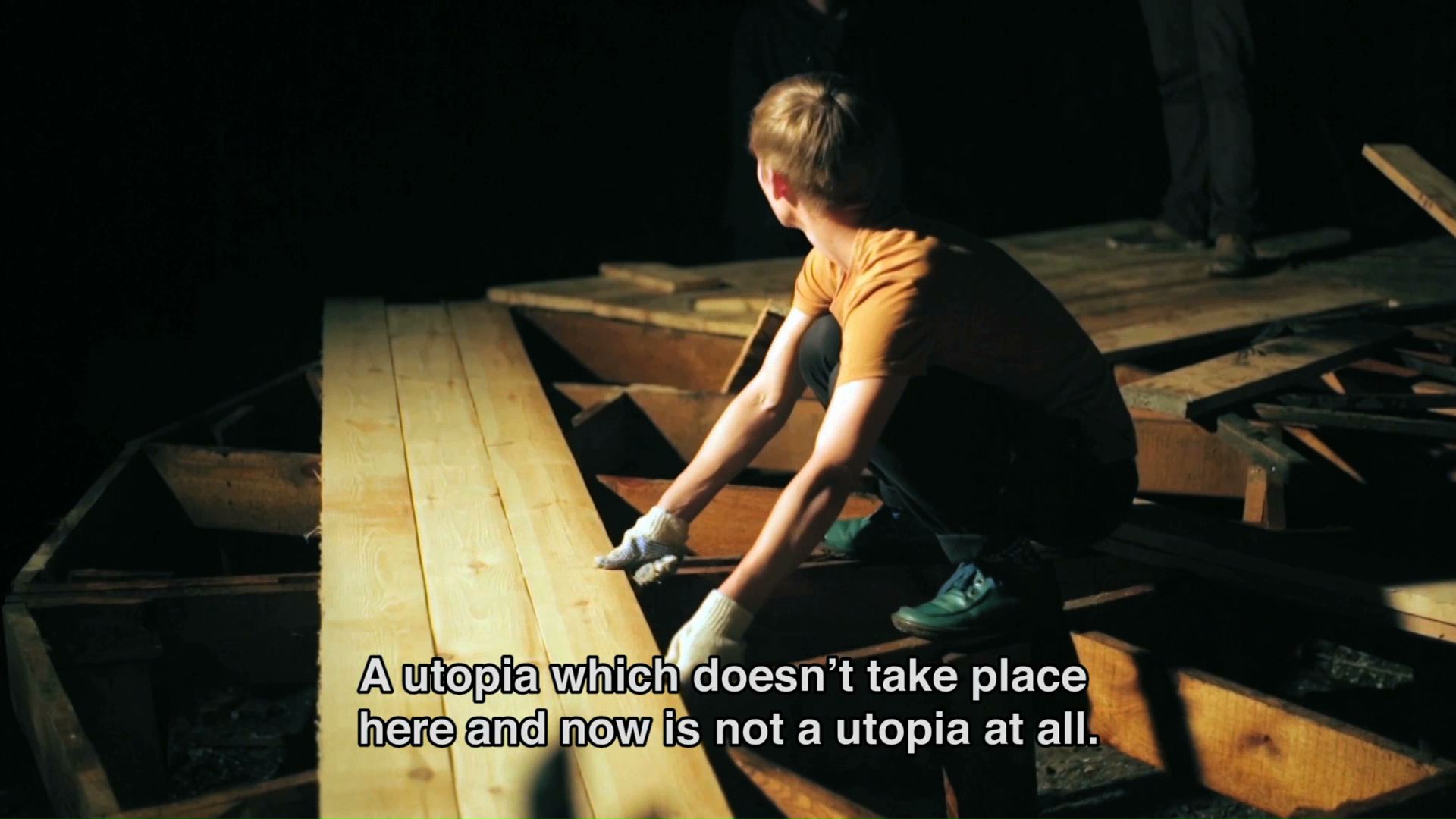

OR: I’ve known most of these people for a very long time and I knew them as interesting thinkers. For instance, some of the conversations we’ve had with an artist Vova Vorotniov over the years ended up being included in the film, but in a completely improvised way, so it is a completely non-staged, documentary film. One of these conversations is about the issue of non-alienated labor, something that unexpectedly came up in a lot of talks and interviews in the film. Because this whole area was an experiment in liberating one’s labor, the small-scale liberation of artistic labor—which is of course problematic because this kind of liberation can’t really work properly if it only happens on a small scale. It only works, if it works for everyone. One of the conversations that was pertinent at that time and maybe still is, maybe even more so, is the question of liberation in the here and now versus the idea of struggle. The idea of struggle is something that is always delayed, and you have to always fight towards some defined goal or situation or state of affairs that probably never arrives, or if it does arrive, it probably comes in a completely different form than what you expect.

Of course, this is a very old debate, roughly, between Anarchists and Marxists, which was reproduced in a way in that environment. There is this anarchist school of thought which claims that the only struggle worth fighting for is a struggle that starts with the here and now. That you should just live your utopia right here and right now and not create the conditions for the better life, something which the Marxist revolutionaries are invested in. So, this then, was an attempt to just start living the life that we would like to live. It was a very short-lived kind of space where this could be possible at least long enough to make a film. Of course, it was super ephemeral, like most of these initiatives are, and basically it only exists in the film. In reality everything was not so bright, and none of us actually liberated our labor for good.

There were people who were talking about labor and the liberation of labor, and there was another faction of people who were just silently doing things—but not in the sense that someone was taking the privilege of discourse while the others had to labor. Doing something was also a statement, so one could make statements by doing things rather than talking. In the film, for instance, an architectural collective called Pylorama are building a construction, a kind of a hybrid space for performance, a venue for the different practices that people in the area were involved with. They are building this open-air venue with an auditorium like a theater, a bit like a small-scale theater of Dionysus in Greece—it is long shot, but it was a small-scale experiment in producing this kind of space. The area evolved in different forms over time, but all of the collaboration on building the theater structure lasted for one month and the filming also lasted for one month.

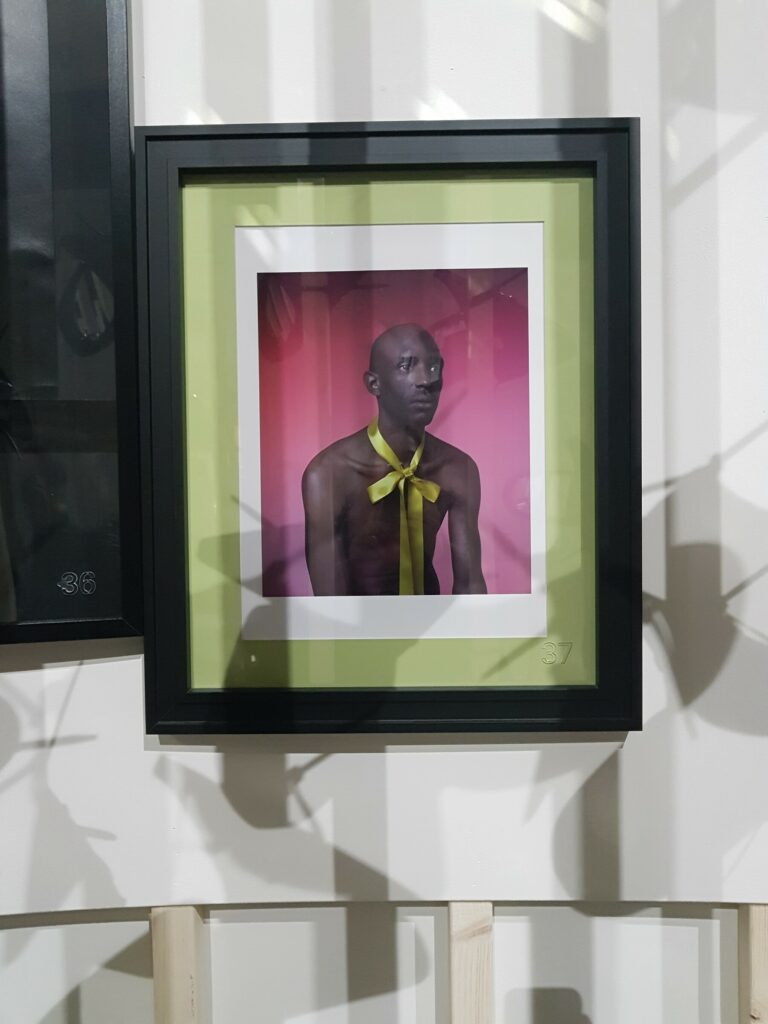

GW: Tell me about the queer performance collective that has a strong presence in the film.

OR: The time of the filming was kind of a special moment in the life of this area because it was joined by Misha Koptev, an artist who had fled from the occupied territories in Eastern Ukraine, from the city of Luhansk. This was a queer artist who for several decades used to run a queer performance troupe in the city. His practice merged theater, performance art, and DIY queer fashion and all this was happening in a quite conservative city in Eastern Ukraine, really close to Russia. Post-industrial or industrial regions sometimes have this homophobic reputation, so it was surprising for me to know that this was the only self-organized queer theater group anywhere in the whole of the country. He has somehow been tolerated there and had some type of venue that was frequented by all kinds of people. But then he had to flee after Russian proxies took over when this region was occupied by actually fascist, ultra-patriotic pro-Russian forces, and then at some point, simply by regular Russian forces. This made his work and existence there impossible.

And so Misha Koptev fled to Kiev and he actually ended up in this cluster of garages, and my collective welcomed him into the venue we used to run, and we turned one of the garages into a kind of a base for his activities. He assembled a new troop from amongst the artists and performers in Kiev, and he started to rehearse with his new troupe there. It was a different situation for the whole cluster, as even though there’s quite a strong queer scene in Kiev, this was something radical, in terms of bodily presence and nudity and all kinds of transgressions that happen during his performances.

GW: It seems that his performances are appropriating the elements of fashion industry and therefore can be easily commododified.

OR: Misha appropriates this language from the catwalk, but he takes it to a different dimension that is undigestible for commercial fashion. He subverts the catwalk completely, so he never had any kind of commercial success and his shows were never commodified. His practice is based on improvised dressing up. He collects and assembles all kinds of costumes, or discarded elements, second-hand stuff, or something that someone would find in the trash and then during the performance they improvise by continuously changing these costumes. And all this cannot really be repeated because these costumes only exist for the several minutes that the performer is on the catwalk. So, I think he is actually avoiding commodification although I’m not sure if he is doing it consciously, it just emerges from the way he works. Although he would not be really opposed to some kind of commodification as a person who is living in poverty.

Before Misha’s arrival, this whole cluster looked a little bit like a hetero lad, graffiti, masculine, slightly macho scene, and it was interesting to observe the inclusion of this really strong queer component. I’ve been cautious about possible homophobic situations with regards to Misha. But as there was this fairly loose vision of what kind of local utopia was going to emerge – his art and his position was totally included. Misha brought a very strong queer spirit to the place. This also contributed to a spirit of sexual liberation, which was already present in the area anyway. Misha was hoping for this place to become a cruising area, which I think happened to some extent.

GW: So was the ampitheater constructed there specifically for Misha’s performance?

OR: The amphitheater was not created for the sake of Misha’s performance, it was basically a collective work by various people and groups who came up with this idea, while Misha’s troupe was on the margins rehearsing, but in the end, it turned out that this spontaneous process led to the creation of a space that would be best utilized by him. It is partly because Misha always does these kinds of site-specific performances, and this place turned out to be the probably his best setting. His performances only make sense to you if you are physically watching them in the here and now. They are an act of ecstatic climax, they cannot really be planned and are to a very large extent improvised. It’s basically about people doing things they truly like to do in life, but they will never admit this to each other or themselves. It’s about a moment of complete bodily and instinctual liberation, a kind of happiness in the here and now, that cannot be reproduced and cannot be really documented. And let’s not forget that before the amphitheater for the Greeks emerged as the site for the Dionysian unconscious, the theater of Dionysus that gave birth to performance out of ecstatic dance and ritual—which then became a way of reflecting the community to itself.