Matthijs de Bruijne

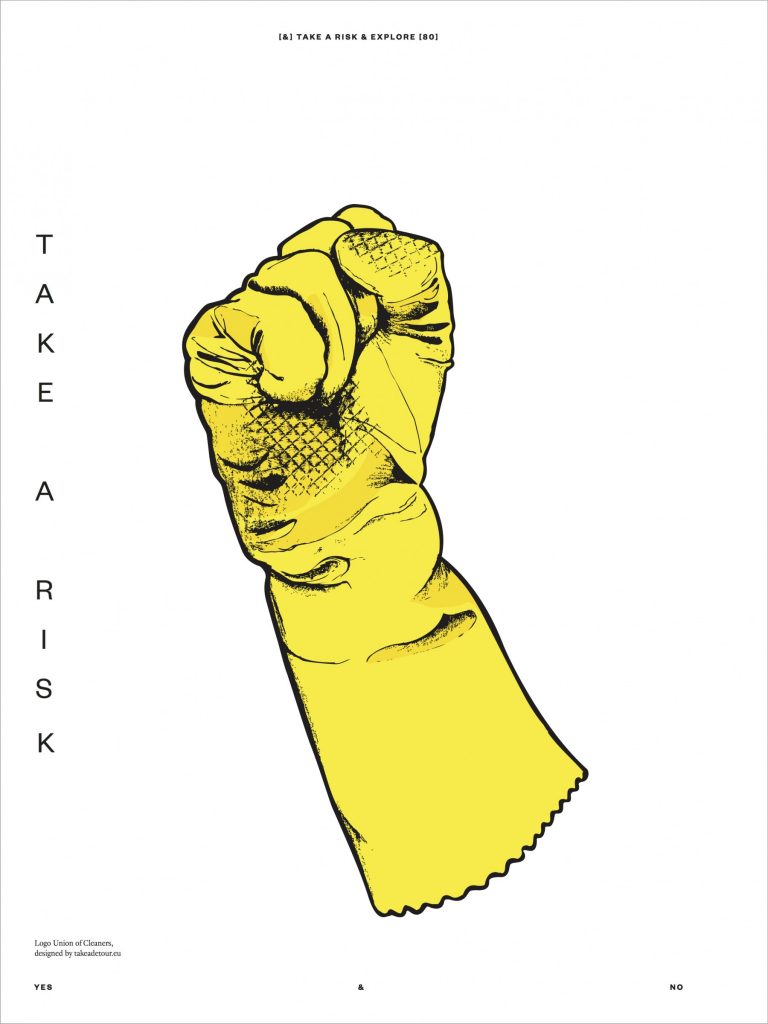

Matthijs de Bruijne’s practice is a result of being in political collaboration with trade unions and labor organizations. Working in Argentina in December 2001 in the middle of social conflict and a bankrupt state, de Bruijne learned that the artist can be more than a reflective outsider and can work within political struggles. He was invited to work as an artist for the Dutch Union of Cleaners and Domestic Workers in 2010, creating their visual identity. An exhibition surveying the breadth of his artistic practice and political collaborations is Matthijs de Bruijne: Compromiso Político at BAK, basis voor actuele kunst, Utrecht, 2018. De Bruijne was a BAK 2017/2018 Fellow. De Bruijne lives and works in Amsterdam.